Nowadays, the prevalence of kidney stones (also known as renal calculus/calculi) has risen, especially in modern society.

Doctors prefer for patients to pass small enough kidney stones themselves through the act of urination. However, the human body often doesn’t take our preferences into consideration. Frequently, patients are unable to pass kidney stones due to the simple fact that they have grown too big. Therefore, without surgical intervention, patients will experience excruciating pain as well as possible life threatening complications in the inevitable event of a blockage.

It is extremely uncommon for a stone situated inside the kidney to cause pain. This becomes an entirely different story when the stone – much like a ripe apple falling from a tree – detaches itself from the interior of the kidney and embarks on a journey to the bladder which is connected to the kidney via a small tube called the ureter. Unfortunately, if the stone is too large to pass it will most assuredly become lodged somewhere along the way, or become stuck on the wall of the ureter; which can have catastrophic and immediate painful ramifications. When the stone lodges in the ureter, the patient experiences colic, resulting in excruciating pain as well as possible medical complications. Pain caused by kidney stones has been described as one of the worst pains a human can experience.

Possible outcomes of a renal blockage…

- Kidney infection

- Kidney damage

- Kidney failure

- Hydronephrosis – When the kidneys are unable to drain urine to the bladder – the urine accumulates in the kidneys. As a result the organ becomes engorged (swollen), which is excruciatingly painful and if left untreated will cause kidney failure and death. The kidney may rupture, relieving the pressure and preserving the organ. Otherwise the raised pressure will gradually destroy the kidney, usually within a couple of months.

Initial treatment is almost always analgesia with narcotic agents and anti-spasmodics, then a scan to assess the position and size of the stone. The urologist will make a decision at that point as to whether the stone will pass with or without surgical intervention.

Obviously, the best solution is when the patient can expel the stone(s) naturally, often with the assistance of medication for nausea and analgesics/muscle relaxants to ease the passage of the stone. Patients will be asked to void urine into a cup-like sieve to catch the stone. This allows the patient to see when the stone comes out and allows for the stone to be collected in order to be sent to a laboratory for analysis. Knowing the composition of the stone assists in preventing the growth of future stones.

If an operative solution is required, the technique used will depend on; stone position, size, hardness and the experience of the urologist.

Operative solutions…

Here are some root word definitions in order to facilitate the reader with understanding the various procedures.

Eg. Nephro–litho–tomy = Kidney stone removal

- “Nephro-“ = Kidney

- “-Litho” = Stone

- “-Tomy” = Removal

- “-Tripsy” = Crushed

- “Lapara-“ = Abdomen (Soft part of abdomen between the ribs and hips)

- “-Scope” = To see

- Extracorporeal = From outside the body

Ureteral Stents

In medicine, the word “stent” can be defined as a temporary splint that is placed within a blood vessel, duct or canal in order to facilitate healing and/or alleviate a blockage.

A ureteral stent is a thin, hollow, flexible tube that surgeons insert into the ureter in order to prevent any blockages forming between the kidney and the bladder. Normally, another stent is inserted after a kidney stone procedure, it helps maintain adequate drainage of fluid from the kidney to the bladder. The stent also ensures that any stones passing from the kidney to the bladder, don’t become lodged in the ureter. Ureteral stents are commonly called, “double J stents” as each end of the stent is curled in order to ensure they remain in place.

There are various types of stents, all serve the same purpose but what sets them apart is the length of time they can be used for. Double J stents are intended for short term use – ideally a few weeks. Whereas, “indwelling” stents such as, Allium stents; can be left in for up to three years.

Risks associated with ureteral stents

- Increased risk of ureteral infection

Ureteroscopy

A minimally invasive method of removing stones from a patient’s ureter, especially ones lodged close to the bladder. Commonly performed in the event that ESWL fails. Ureteroscopies are commonly performed under general anaesthesia.

How is it done…

A long, thin, flexible tube known as an ureteroscope (essentially the same as an endoscope) is passed through the urethra and bladder in order to access the ureter(s). The ureteroscope has a light and camera on one end so surgeons are able to visualise the inside of the patient without making a single incision.

There are two types of ureteroscope; semi-rigid and flexible. Semi-rigid scopes are often used for removing stones in the lower ureter, but can be used in the upper ureter if it is dilated enough to allow safe passage of the semi-rigid scope. Hence, a flexible scope is safer and less likely to cause trauma above the pelvic brim.

A flexible ureteroscope is used to remove stones in the kidney too small to address with ESWL.

Once the stone has been located, the urologist will discern whether or not the stone is small enough to be removed whole; or if it needs to be fragmented using a laser.

Baskets

An instrument called a “basket” can be introduced along side the ureteroscope in order to grab and remove any stones or debris from the kidney, ureter, bladder or urethra. The basket resembles the wire end of a whisk, which can be extended and retracted inside the patient safely and with ease. In addition, some patients may also require the insertion of a stent after the procedure; at the discretion of the urologist.

Patients can expect to be discharged on the same day as the procedure, provided there were no complications or unforeseen findings. Typically, regular daily activities can be resumed 2-3 days after the procedure.

Risks associated with ureteroscopy

- Ureteral stent discomfort

- Ureteral wall injury

- Stone migration

- Infection

- Bleeding

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL)

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, or ESWL, is the least invasive form of kidney/ureteral stone removal; performed under general anaesthesia.

How is it done…

This treatment modality relies on a machine called a lithotripter to generate high-energy shockwaves that are directed at the kidney/ureteral stone. Consequently, the shockwaves reduce the stone(s) to smaller fragments; the goal is to reduce stones to small enough sizes in order for the patient to safely expel them through urination.

For this nonsurgical treatment, the shockwaves are administered to the body via a soft water filled casing. The patient is positioned with the area intended for treatment placed against the casing which pulsates with each shockwave.

If the surgeon feels that the stone fragments are still too large to safely and comfortably pass, a uretroscopy can easily be performed to remove the fragmented stone. Doctors prefer ESWL as it eliminates the need to make any incisions in the patient.

Patients can expect to be discharged on the same day as the procedure, provided there were no complications or unforeseen findings. Typically, regular daily activities can be resumed 2-3 days after the procedure.

What makes a patient unsuitable for ESWL

Being the least invasive treatment modality for kidney stone removal, doctors would ideally rely on ESWL the most. However, there are certain factors that can make a patient an unsuitable candidate for ESWL.

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Bleeding disorders

- Severe skeletal abnormalities

- Kidney cancer

Practitioners may be hesitant to suggest ESWL if…

Some factors may not exclude patients as candidates entirely, however practitioners may be cautious when considering ESWL as a treatment option. These factors include…

- Chronic kidney infection

- Scar tissue in the ureter

- Stones consisting of cystine or calcium

- Stones that need to be removed immediately

- Having a cardiac pacemaker

Risks associated with ESWL

- Bleeding around the kidney

- Urinary tract infection

- Blockage of urinary tract from stone fragments

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL)

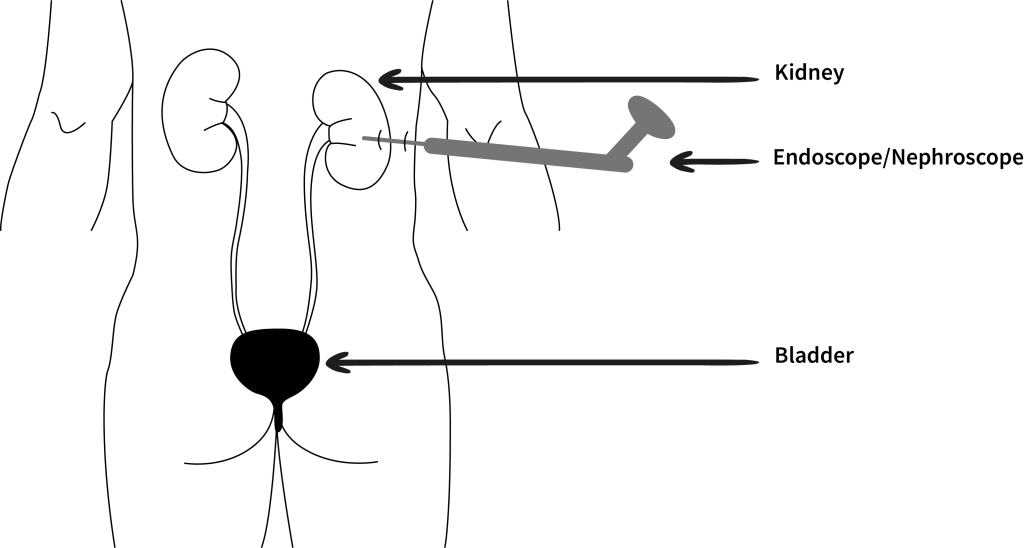

A percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL/PNL) is a form of treatment generally reserved for the larger kidney stones (20mm and bigger) or “staghorn” stones. Practitioners will also opt for this surgery in the event of ESWL/ureteroscopy failing or proving to not be viable. PCNL is performed with the patient under general anaesthesia.

How is it done…

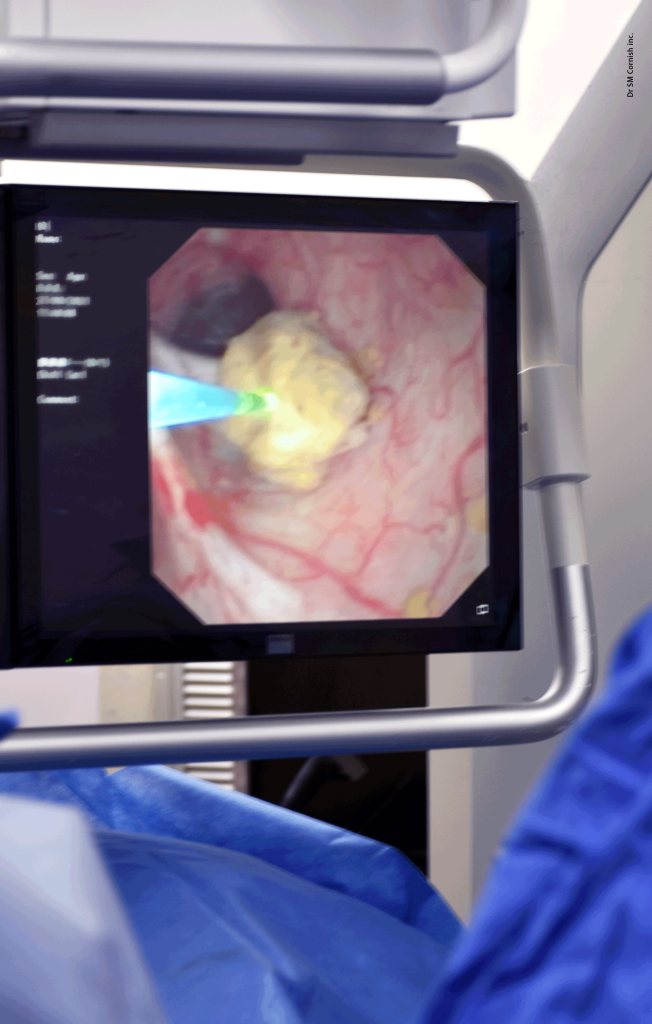

In order to perform a PCNL, an incision is made in the patients flank over the kidney. A guide wire is inserted into the kidney under x-ray guidance through the incision. Graduated sheaths are placed over the guide wire to incrementally enlarge a tract directly to the kidney from the skin. Finally, a nephroscope is introduced into the kidney along the tract and the stone can the be visualised.

If the stones happen to be too large to remove whole, a laser can be used to reduce the stone to smaller fragments.

Patients can anticipate a 2-3 day long hospital stay after the procedure. Furthermore, they may require 1-2 weeks to recover in totality from the procedure.

Risks associated with PCNL

- Bleeding

- Renal pelvis perforation (Formation of a hole in the kidney)

- Hydrothorax (Accumulation of fluid around the lungs)

- Infection

Laparoscopic Ureterolithotomy

The main purpose of this procedure is to remove larger stones lodged in the ureter. In most cases, this procedure is only performed when less invasive methods fail. Laparoscopic procedures are performed under general anaesthesia.

How is it done…

Small incisions (generally 0.5-1.5cm long) are made in the patient’s abdomen, into which a laparoscope and carbon dioxide gas supplying tube is inserted. The laparoscope is similar to that of a endoscope; however, they differ in that the optic tube is not flexible. Why fill the abdomen with gas? By doing so, more space is created in the abdominal cavity, which makes it easier for the surgeon to access and visualise the patient’s internal organs.

Additional small incisions will be made in order to insert the operative instruments. The surgeon will use a cutting and a grasping tool. Using the optic scope, the surgeon locates the affected kidney and ureter; a small incision is made in the ureter in order to remove the ureteral stones. Finally, once all stones have been removed, the ureter is then stented and sutured closed.

Upon completion of the procedure, the gas is released from the abdomen of the patient and all small incisions in the abdomen are sutured closed.

Patients can expect a hospital stay of 2-3 days granted no complications arose, and regular daily activities can be resumed within 2-3 weeks.

Open Surgery

Open surgery for kidney stones is the most invasive form of treatment and is considered to be the last resort if all other options fail. All open surgery is performed under general anaesthesia

How is it done…

Open surgery is only performed when alternative stone removal methods fail or prove to be insufficient. Surgeons may also have to resort to open surgery if the stones are abnormally large, especially in the case of “staghorn” stones. Furthermore, patients born with a defect in their urinary system may require open surgery too.

To perform this surgery; once the patient is safely asleep, a large enough incision is made in the patient’s abdomen or side in order to expose the affected kidney and ureter. Wound retractors keep the surgical site open whilst the team operates. The surgeon will then make an incision in the organ, allowing access to the stones that need to be removed.

Once all stones have been removed, and any repair work is completed; the surgeon sutures the kidney closed and then does the same for the abdominal/flank incision.

Prior to closing, a catheter may need to be placed in the kidney. By doing so, urine can be drained from the kidney as the organ heals.

Patients can expect a hospital stay of 6-9 days and a recovery period of 4-6 weeks.

Risks associated with open surgery

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Adverse reaction to anaesthesia

- Increased chance of hernia developing at the incision sites